The New York City Symphony and Leonard Bernstein

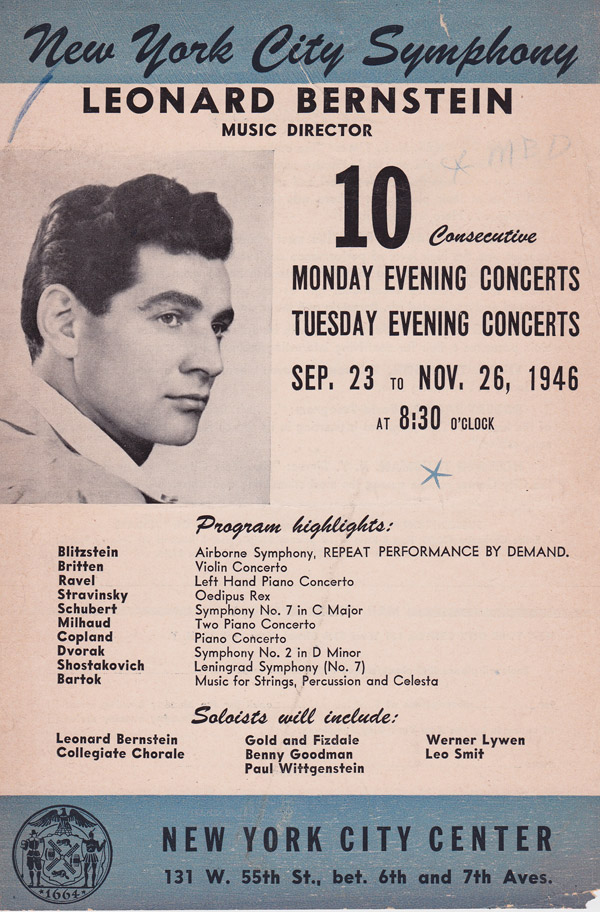

New York Symphony Program.

How does one lose a symphony orchestra? I mean totally lose track of an amazing ensemble located in the heart of New York City, giving several seasons of stirring performances at the City Center on West 55th Street; a band designed to be "the people's orchestra", that was the godchild of two memorable 20th century municipal executives, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and City Council President Newbold Morris; and to boot, an orchestra whose founding music director was Leopold Stokowski, immediately followed by the three-season directorship of the 26-year-old Leonard Bernstein.

I realize that the New York City Symphony's short life (1944-48) took place before the advent of databases and gigabytes, and that even at the peak of its existence, it was a shoestring operation, always barely able to make its modest payroll and unable to afford such luxuries as an archive, let alone an archivist, as do our major orchestras. But to disappear completely from the public record, after what must be counted as a very major achievement, both musical and sociological, seems a great shame.

The Google links to Leonard Bernstein are ample. Almost all of the references are cross-linked so that, for example, one may click on any of the myriad citations and gain direct access. But while it acknowledges that Bernstein was music director of the New York City Symphony, the name of this organization appears not in linkable blue but in ordinary black, utterly unlinkable type—a researcher's dead end and an invitation to oblivion.

In fact, the New York City Symphony had a forerunner, also a pet project of the musically sensitized Mayor La Guardia. It was an offshoot of the Roosevelt-inspired WPA and gave its concerts in Carnegie Hall under a diverse group of conductors, including Otto Klemperer and Sir Thomas Beecham. Its official name was The New York City WPA Symphony Orchestra and it survived for only 3 1/2 years, the final stretch under the leadership of Emerson Buckley. And to make matters even more confusing, there exists to this day an outfit legally entitled City Symphony Orchestra of New York, Inc. but presenting under the name New York City Symphony. Originally an amateur group founded in 1926, it was revitalized and incorporated in the 1950s and performs intermittently under the direction of David Eaton.

The only such entitled ensemble with which Leonard Bernstein was affiliated has been described in Humphrey Burton's excellent Bernstein biography, as well it might be since this New York City Symphony became Bernstein's very first orchestra of his own. Never mind, Burton tells us, that the music director was unpaid, receiving only a meager stipend for expenses; or that he was given only a few weeks lead time to plan an entire first season. The fact remains that he was free to engage eager young players and to put his fecund imagination to work in putting together the most exciting and unusual programs the city had ever heard. For the truly modest price of admission—two dollars for the best seat in the house, seventy-five cents for the balcony—audiences could enjoy twelve Monday nights or six Tuesdays at 6 p.m. ("giving workers an opportunity to hear some good music on their way home, after a sandwich and before dinner") of a unique mix of the classics and the unexpected.

In its first season, the orchestra had given 30 performances and Stokowski was making ambitious plans for a second season, to include the Beethoven Ninth and Mahler Eighth in his programs. But between the conclusion of the maiden season and the onset of Year 2, something happened to make the old maestro think the better of it. In all probability, he had been looking for financial support that was not forthcoming. At any rate, it was not until late August of 1945 at Tanglewood that Leonard Bernstein was notified of his appointment to take over the New York City Symphony whose season was to commence on October 8th and include, in addition to staples, Stravinsky's Symphony of Psalms, Chavez's Sinfonia India, and Ravel's Schéhérazade, concluding with Marc Blitzstein's Airborne Symphony.

Although Bernstein's initial season was a brilliant success, he immediately ran afoul of politicos. Never one to mince words, the youthful conductor made the pages of The New York Times, lamenting that the orchestra had "no economic security." "When I travel around the country," he said, "people always come up to me and ask me what they can do to give their cities a civic orchestra like New York's, and I look at all these people in amazement and wonder what they are talking about. 'Can't you realize that it is a complete fraud?' I always tell them. I hasten to assure you, in front of all these people, that it's a fraud. We haven't a penny from the city."

Although he tried to sweeten the pill by acknowledging the Mayor's good intention and calling him "a wonderful guy," the damage was done and La Guardia let him have it. "I am very fond of Mr. Bernstein and I am sure he will on reflection see that he was unfortunate in his choice of words," he said, explaining that the City Center lost money every week and that its symphony orchestra needed to be "self-sustaining."

The brouhaha quickly passed and Bernstein went on to his second, and then to his third, season which opened with a program featuring the "Palestinian composer," Manuel Mahler-Kalkstein—remember, it was 1947 before there was an Israel, and the 39-year-old was a blood relative of Gustav's—coupled with the latter's Second Symphony ("Resurrection"). Reviewing in The New York Times, the acerbic Howard Taubman wrote: "It will serve no purpose at this date to argue the case of Mahler. Those who find Mahler a stirring experience have the right to keep on finding him so; those of us who wish he had had either a good editor or more self-criticism have the right not to listen to him. The pity of it is that the choice has to be one or the other. There are pages of poetry and grandeur and a shy, sensitive wit in this symphony. But, oh, the length of it!...Mr. Bernstein made the Mahler symphony as dramatic as he could, sometimes dramatizing it excessively. But it was lively, crisp, mettlesome playing. Now if Mr. Bernstein will be good enough to start his programs when they are announced to start, instead of fifteen minutes later, we may look forward to a rewarding ten-week season by the New York City Symphony."

A series of bizarre happenings occurred at the conclusion of the 1947-48 season, and once again, money was the cause. Still no funding was coming from the City and whereas Local 802 of the American Federation of Musicians had made a contribution in prior years, this support was terminated. In protest, Bernstein resigned, writing: "Rather than a reduction in budget, I had for three years been looking forward to an expansion, which I feel is now necessary. By expansion I mean an increase in the number of concerts given (with resultant increase in financial security of the orchestral members), an increase in the size of the orchestra and an increase in the length of the season.... I have, therefore, tendered my resignation with reluctance and sadness." That was in March. By May there was a half-hearted attempt to smooth the waters, Bernstein withdrawing his resignation and Newbold Morris grudgingly writing: "We were prepared to continue this fall with the orchestral concerts except that Mr. Bernstein felt compelled to accept the invitation of the Palestine Symphony Orchestra to be its conductor at this time. I am thoroughly understanding of his feeling in this matter, and he is being granted a leave of absence, but will resume as director of our symphony season in the fall of 1949, and perhaps even earlier, in the spring of that year, if the time can be arranged."

Right from the get-go, Bernstein's adventurous programming made other (and richer) orchestras look staid and tradition-bound. Opening the 1945-46 season with a mix of the new (Copland An Outdoor Overture, Shostakovich Symphony No. 1) and standard repertory (Brahms Symphony No. 2). Who else would have dared to pair the Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 6 with shorter works by John Lessard, Alex North, Vladimir Dubelsky, and Samuel Barber? And how about the soloists Bernstein attracted? Samson François (Prokofiev Piano Concerto No. 5), Isaac Stern (Haydn and Szymanowski Violin Concertos), Leo Smit (Haydn and Copland Piano Concertos), Ella Goldstein (Rachmaninoff Third Piano Concerto), Paul Wittgenstein (Ravel Piano Concerto for the Left Hand) and Bernstein himself conducting and soloist (Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 1).

To the best of my knowledge, there exists no record of concerts by the New York City Symphony after 1947-48 season. I find no press release, no news story, no obituary announcing the demise of the New York City Symphony and must assume that it died a quiet and unheralded death. If it even existed for another season or two after the departure of Leonard Bernstein and, if so, under whose aegis seems doubtful. Chances are that the municipal administrations after La Guardia no longer even lent it moral support, and that Newbold Morris, who had become top dog at City Center lost patience with his young firebrand of a music director. My guess also is that a lot of people simply got tired of working for nothing or next to nothing. And of course that young firebrand soon went on to bigger and better things, leaving a large vacuum where his inimitable energy had been.

Whatever the reason for the short, happy life of the New York City Symphony, it was a life worth remembering and, at least for a few years, a unique segment in the life of Leonard Bernstein and a component to the cultural life of the City.

|