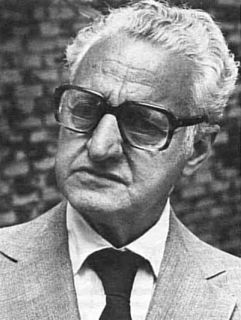

ENCOUNTERS by George Sturm

Paul Fromm

But when was your 75th birthday?"

we asked Paul Fromm, having failed to find a listing of one of the world's

great music patrons in any of the reference works we had consulted. "No

one knew it in Chicago, either," he said. "I tried to tiptoe my

way through it." (It actually was on September 28, 1981.) His wry wit

and profound wisdom are hallmarks of the man who, thirty years ago this spring,

resolved to make his money in the wine business and spend it in music.

The Fromm Music Foundation was established in 1952 and

the number of contemporary composers who have benefited from its largess

is approaching the 150 mark from commissions alone. In addition, the Fromm

Music Foundation, jointly with various musical institutions, has sponsored

many concerts and festivals; has been a principal patron of the Contemporary

Chamber Players in Chicago; has stimulated and subsidized recordings and

radio programs devoted to contemporary music; has organized and sponsored

fellowship programs in music criticism; has, from 1962 to 1972, funded the

journal Perspectives of New Music; has sponsored since 1956, jointly

with the Berkshire Music Center, the extensive contemporary musical activities

at Tanglewood; and, with a view to perpetuity, has established the Fromm

Music Foundation at Harvard University, quoting John Maynard Keynes in its

very founding statement: "The task of an official body in the arts is

not to teach or censor, but to give courage, confidence and opportunity to

artists."

Born in the small Bavarian town of Kitzingen, Paul Fromm

recalls that "if you wanted to hear music, you had to make music."

His family was musical and, by the time he quit school to go to work in Frankfurt,

he had become a proficient pianist. "In those days, there were transcriptions

for piano, four-hands of just about everything, and my brother Herbert and

I had the repertory in our fingers and our ears. We were five children and,

except for one, we all sang or played, so you see that music has been a lifetime

passion. When I lived in Germany, I went to Donaueschingen every year and

heard the music which was being written by Bartok, Hindemith, Schoenberg,

Stravinsky and the so-called avant-garde of the time. We weren't passive

consumers but active participants in music-making, and we were not the exception.

Every professional person was deeply steeped in the humanities. The prospects

of a new book by Thomas Mann or a new painting or musical work generated

unbelievable excitement and made our adrenalin flow. Today we live in a technological

society in which we can go to the moon without knowing or loving Beethoven."

The Fromm family's wine business was established in 1864.

When the political climate of Germany grew increasingly troubled, an American

client suggested that young Paul go to work for him in Chicago. He arrived

on July 4, 1938, and, witnessing the Independence Day festivities, thought

that revolution had broken out. Six months later, he began his own firm on

the $1500 savings he had been able to bring out of Germany. Here, in the

New World, Paul Fromm began to cultivate his twin legacies: the wine importation

business and his total commitment to music, and most particularly the music

of his own time. "It is not enough to support the artist," Fromm

says. "It is even more important to nourish the artistic spirit. Our

composers over the last thirty years must have felt lonely at times. We have

tried to make them feel that they are not alone in the world. We do concern

ourselves with individuals and individual issues, rather than with anonymous

aspects of cultural life."

Was it not tricky, we asked him, to exercise so much judgmental

responsibility? How does one determine what is beautiful? "If you are

in search of masterpieces, and if you weigh the music you hear on the illusory

scale of masterpiece probabilities, I would have to say that the masterpiece

will always elude you, because posterity must make the ultimate judgment.

The only reliable tool to assess intrinsic artistic merit is historical perspective."

Composers today generally support themselves from activities

other than composing. Most teach, having found an economic haven in academia.

We asked if he thought this has been good for them. "I doubt it. We

give them economic security, but we also quarantine them in a world which

has no connection with the real world. The environment of the university

is probably not the most wholesome. Even within its confines, the composer

is not given a forum outside of the parameters of the music profession. But,

do we want our composers to starve to death?"

Paul Fromm's illuminating remarks to the governing boards

of the Boston Symphony Orchestra were reprinted under the title "The

Role Of Symphony Orchestra Boards" in Symphony Magazine (October/November

1981). He stated: "In the last analysis, music exists for the audience."

He amplified: "Audiences are never homogeneous. There's something almost

mystical about them. In the long run, though, audiences must always be reduced

to individuals, because the artistic experience gives rise to individual

response. The performer's function is to inform people, to involve them.

But, as Chekhov wrote in a letter, `You cannot bring Gogol to the people;

you must bring the people to Gogol.' What now passes for music education

is often limited to Christmas carols and marching bands. A humanistic society

accepts its responsibility to teach music as a fundamental component of education."

Fromm has clearly formed ideas on the do's and don'ts of

programming. "We should not play unproven contemporary works in juxtaposition

with the masterworks of the past., In exactly the same way, it would be unfair

to present to the public a portrait of Beethoven by playing his feeble Battle

Symphony on a program with The Rite of Spring. The only way to

integrate 20th century music into the mainstream is for performers and conductors

to play contemporary music which they really love. The wholesale diffusion

of contemporary music is really not a commitment, but almost like social

aid based on the concept of charity to the poor. That's O.K. for social work,

but not for cultural support. Think of the great conductors of the past,

of Bruno Walter, or Beecham, or Koussevitzky. They championed composers and

played their works over and over again. That was commitment. That is the

only way to establish contemporary repertoire. Let's begin with the early

decades of our century, and let this music serve as a frame of reference

which will lead us up to the present."

Paul Fromm cannot imagine "a good life" which

is not steeped in "humanistic aspiration" and fears that a society

without the broadbased ideological tenets of humanism promotes robots and

automatons. A good patron of the arts, he says, "must have respect for

the dignity and supremacy of the creative personality. He must understand

that music would cease to exist without constant regeneration and rejuvenation.

A good patron must feel himself to be an active participant in the creative

process. The musical experience is a unique interaction between composer,

performer, and listener, based on a certain intensity of concentration. The

patron should seek to facilitate that intensity."

Given his own guidelines, Paul Fromm has accurately defined

and described the unique contribution he has made to the contemporary composer

and, ultimately, to the spirit of the music of our time.

|