Luigi Dallapiccola On Opera

Twenty-fine years ago, in the spring of 1957, an "Opera Institute for

Conductors" was held at The Juilliard School. Among the workshops, seminars

and sessions of the two-week period a composers' symposium was planned and

invitations went out to Roger Sessions, Luigi Dallapiccola, Ernst Krenek,

Edgard Varese, and Aaron Copland. On April 16, 1957, Dallapiccola delivered

the remarks published here for the first time.

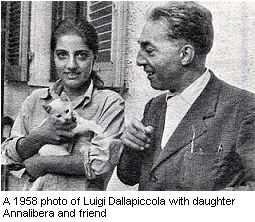

Luigi Dallapiccola was widely regarded as one of this century's great composers.

David Drew's short tribute in In ricordo di Luigi Dallapiccola begins:

"Until his death in February 1975 Luigi Dallapiccola was continuing

to add to the small store of 20th century works that seem destined to survive

as classics. His music had long possessed those qualities of creative imagination

and character which, over the centuries, have proved more enduring than any

style or idiom. It was surely in that sense, rather than simply to identify

the city in which he lived, that contemporaries would refer to him as 'the

Florentine Master.' "

Dallapiccola's influence, however, was as uniquely manifest in his humanism

as in his composition. No one who knew him could fail to note the depth of

his dualities: the present and the past, God and man, war and peace (in all

their many senses), and man's primordial destiny, even responsibility, to

struggle. It was, no doubt, his lifelong commitment to resistance which generated

a compassion for human suffering. Small wonder, then, that he was as drawn

to opera as an art form as he was!

What David Drew writes about Dallapiccola's music applies

equally to Dallapiccola's life: "... it simply seems glad to be alive

because it is working not for itself but for mankind, in search of Freedom,

of Order, and of God."

I shall begin by saying that I cannot agree with that modern trend which considers opera chiefly as a spectacle or a show.

If what we have in mind is not a "musical" but opera proper, it is evident that its essence is in the music.

I will not insist especially on the Italian "melodrama," in which the libretto was the mere outline of a plot. Such librettos, as everyone knows, were linguistically very poor. (The last opera that Verdi, in 1857, still called a "melodrama" was Un ballo in maschera.) As to Arrigo Boito's libretto for his Otello, it is evident that his version of Shakespeare's masterpiece could never be staged as a drama without ridicule. Shakespeare's text, as Boito shortened it, is revitalized by Verdi's immortal music. On the other hand, to put to music Shakespeare's original text would have been sheer nonsense. In Shakespeare's poetry, every

word has its own accent, meaning, shading; to all of which music-any music-could not add an iota, but rather irreparably detract from them.

I will limit myself to this example, my time being short; but I could say the same of the libretto of Mozart's "Figaro".

The conductor who undertakes to stage an opera, old or new, will have, first of all, to keep an eye on the stage. To write an opera is not at all the same thing as to compose a symphonic poem with solos and possibly chorus. The conductor will then have to keep the stage constantly in mind: that is, the breath of his singers, their gestures, and the mass-movements of the chorus: all this, of course, agreed upon with the stage-director and with the set-designer.

On the stage, an awkward movement or a wrong spotlight can be as fatal as a wrong tempo. A good staging of an opera may well contain some slight imperfection on the part of the orchestra; conversely, an opera can be horribly staged even if the orchestra plays excellently.

In this respect I am reminded — indeed, with undiminished horror — of some productions of Wagner's operas I saw in Italy when I was young. The orchestra conductor thought he was conducting a concert: he gave all his care to the orchestra, while neglecting the singers and the stage; at

times he would go as far as to forget that voices must be heard too. It was, then, the period of the "symphonic Wagner": a misconception which retarded for decades an accurate understanding of the spirit of Wagner's operas.

A conductor who wants to capture and express the unfolding line of an opera must rely on an assessment of the respective scenic, verbal and musical elements, and then attempt to synthesize them.

The rhythm of the opera is altogether different from the rhythm of a symphony. This should be kept in mind if the correct delicate relation between tempo and volume is to be established and maintained. The problem, no doubt, is a complex one; I can only hint at it.

If I may be permitted a personal example, I will offer you the following: In the three-stanza aria of my opera The Prisoner — the aria called "Sull' Oceano, Sulla Schelda" — I intended to give the listener the impression of the same motion throughout; I was therefore forced, in the second stanza, to slow down the fundamental tempo from  = 69 to = 69 to  = 66;

in the third stanza, from = 66;

in the third stanza, from  = 66 to = 66 to  = 63, while the polyphonic texture became thicker. = 63, while the polyphonic texture became thicker.

This is but one example. If the metronome has no exact prescription to offer, the orchestra conductor will have to solve each problem relying on his instinct as well as on his musical taste.

Another essential point concerns the pauses between one passage and another, above all in operas with closed forms. At times the conductor will have to tamper with the text, taking off a hold, if the stage situation or the musical situation so require.

I have not forgotten (I am sure I never will) an effect Maestro Vittorio Gui once obtained in the first finale of Verdi's Simone Boccanegra. When the hero bursts out with the word "Fratricidi!" Verdi marked a hold before starting the arioso "Plebe, patrizi, popolo — dalla feroce storia" on which the concertato begins. Maestro Gui took off the hold; and this trifling change gave the whole finale concertato literally a new life.

It is said that the Italian public has never really taken to Mozart's operas, and perhaps it is so. (Obviously, I can only speak with some measure of authority of the audiences of my own country.) But since new stage techniques made it possible to present Don Giovanni or The Magic Flute without long pauses in between scenes, Italian audiences began to enjoy Mozart's operas as much as they are enjoyed elsewhere. A four or five minute interval between the Graveyard-scene in Don Giovanni and its finale used to prove fatal for the rhythm of that opera. (I say "four

or five minutes," supposing that the conductor had been brave enough to dispense with the aria "Non mi dir".)

All that happens on the stage must be a function of the music. Music, I repeat, remains the dominant element in an opera.

While we keep this principle well in mind, it may however be necessary to compromise here and there.

The staging of an opera is teamwork; it requires more than collaboration, namely, brotherly feeling. Its main enemy is the ambition to shine all alone, which unfortunately too many stars of our strange firmament prefer to nurse.

The fascination of the theater rests, I believe, on its very complexity. If a well rehearsed concert has a ninety-nine percent chance of being successful in performance, this is not always true of an opera. On the stage every night is a fresh start and a new risk. Every night is a gamble with perfection at stake — a difficult gamble, with high stakes, indeed. It is an adventure as perilous as it is unequalled.

I feel pleasure and comfort in talking over the problems of opera at a time when, though many new opera houses are being built, the old refrain is still echoed from many sides: Opera is dead.

And it is also a great comfort that our meeting should take place at the Juilliard School of Music, an institution to which the composers of our time owe a heavy debt of gratitude which I am happy to share.

This is not the place to draw a balance sheet of the operas of the twentieth century and to weigh their chances of survival. It should be sufficient to know and feel that there are operatic works of our time. Should somebody come up with the objection that the enduring works of our time are not many, my reply will be that, during the 18th and 19th centuries, in Italy alone, no less than 6,000 operas were composed and produced. How many of them are remembered? Triumphant artistic achievement is always supremely rare. I am convinced that this is as true of our time as it is of the past.

Let me finally send my greetings and my wishes to all the young musicians who work in the field of opera, that fascinating field — in which ordinary people express their feelings by singing heroically-and which is fascinating because it is absurd.

L.D.

|